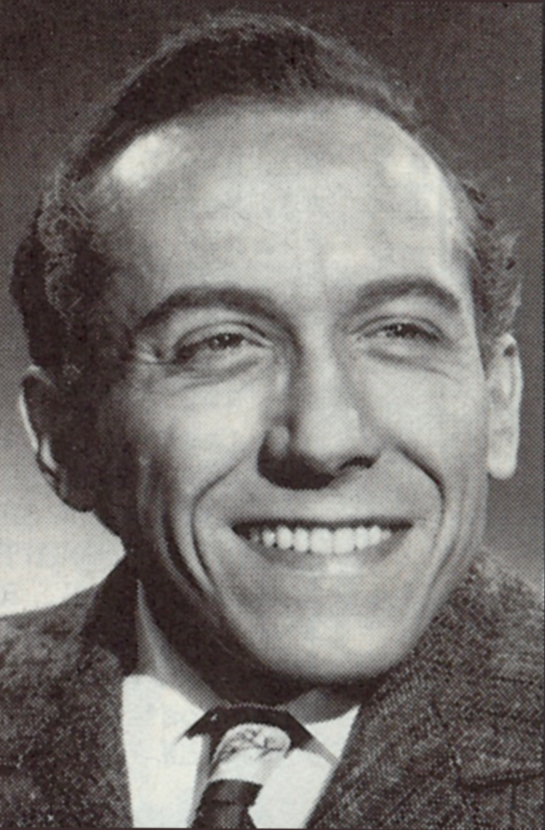

Michael Dunn (October 20, 1934 – August 30, 1973) was an American actor and singer who shunned the usual "cute" typecasting of dwarf actors and sought serious roles requiring dramatic skill. He was a trailblazer who ultimately inspired a generation of dedicated actors with extreme short stature, including Zelda Rubinstein, Mark Povinelli, and Ricardo Gil.[1]

He was a dwarf (in the medical sense of disproportionate short stature) as a result of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia (SED, subtype unknown), a genetic defect of cartilage production caused by a mutation in the COL2A1 (type II collagen) gene. This disorder, classified as a skeletal dysplasia, caused distorted development of his limbs, spine, and ribcage and led to early, widespread osteoarthritis and constricted lung growth. As an adult, he stood 3' 10" and weighed about 78 pounds (117 cm, 35 kg). During Dunn's lifetime, his condition was described by the nonspecific term "progressive chondrodystrophy," or alternatively as "achondroplasia," a term that now refers specifically to a skeletal dysplasia caused by a defect in the gene for fibroblast growth factor receptor 3.1

He was born Gary Neil Miller to Jewell Miller (née Hilly) and Fred Miller of Fargo, Oklahoma in Shattuck, Oklahoma, during the time of the Dust Bowl drought. He was an only child. When he was four, his family moved to Dearborn, Michigan.[2]

Dunn was gifted intellectually and musically. He started reading at age three, was champion of the 1947 Detroit News Spelling Bee—representing Wallaceville School in Wayne County—and showed early skill at the piano. He enjoyed singing from childhood, loved to draw an impromptu audience (even while waiting for a bus), and developed a pleasing baritone and superb sight-reading skills.[3], [4], [5] His parents defied pressure from school authorities to sequester him in a school for disabled children and staunchly supported his talents, independence, and integration into mainstream society. "I always got thrown out of classes for being too lippy," he commented about his experience with elementary school teachers. "I'd read more than they."[6] His orthopedic condition greatly limited his mobility, but he swam and ice skated in childhood and remained a skilled swimmer throughout his life.[7], [8]

He attended Redford High School in Detroit (1947-1951), then entered University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in September, 1951, just before his 17th birthday. However, according to his Columbia Studios press kit biography, his studies were interrupted when he was knocked down a flight of stairs during a "student rush," which resulted a three-month hospital stay.

In 1953, he transferred to the University of Miami, College of Arts and Sciences, which offered a better climate and more accessible campus. His transcript shows that, despite scoring at the 97th percentile of ACE placement exams and the 99th percentile of the CTS English test, he did not distinguish himself academically. However, he was a high spirited and well known figure about campus who sang in the talent show and facetiously joined the football cheerleading squad. Archives at that university's Otto G. Richter Library show that he became first a copyeditor and a contributing writer, then managing editor in 1954 of the college magazine, Tempo. His classmate John Softness recalled, "He could sing like an angel, and he could act and he could write and he was a brilliant raconteur." Softness ran a campus-wide advertising campaign called "Wheels for Gary," which brought in enough money from student donations to buy a used 1951 Austin outfitted with hand controls, so that Dunn could get around independently.1

At various points, he held different odd jobs—singing in a nightclub, answering telephones for the Miami Daily News, and working as a "hotel detective." ("What a gaff! I got my room free and all I did was play cards with the night clerk and keep an eye open for any funny business in the lobby. Who would ever suspect me of being a detective?")7 He left college in 1956 after completing only his sophomore year, returned to Michigan, and attended summer classes at the University of Detroit, in 1957.

Dunn had converted to Catholicism (probably from Methodism-Episcopalianism, judging by his parents' marriage certificate) and was baptized on September 25, 1954, by Rev. J. M. O'Sullivan at Church of the Little Flower in Coral Gables, Florida. He was living in Ann Arbor with his parents, working as a professional singer, at the time he entered St. Bonaventure Monastery in Detroit, on February 25, 1958.[9] According to Brother James Wolf, Provincial Archivist, Dunn entered with the intention of becoming a Capuchin non-ordained Brother. A testimonial from John F. Bradley, Catholic Chaplain, University of Michigan, states: "He has always been interested in Catholic activities and was president of the Newman Club in another school." In response to a question on the monastery application asking: "How long have you been thinking of entering religious life?" Dunn wrote, "More than three years." Dunn was later quoted in the New York Post explaining that he had wanted to be of service, since he was unfit for the military: "Everyone my age was going to Korea and I had this feeling that singing wasn't exactly doing my part."6 However, monastery records entered by the Master of Novices show that the physical demands of monastic life in a huge, 19th-century building with no elevator proved too strenuous. Dunn left of his own accord on May 8, 1958, in order to pursue a stage career in New York.1

In New York, Dunn re-encountered Softness, who volunteered to be his manager. He also befriended actress Phoebe Dorin in an off Broadway show, "Two by Saroyan," in which both had small parts in the early 1960's. They began singing together casually after their nighttime performances, sitting on the wall of the fountain opposite the Plaza Hotel, and drew a following. Eventually, on the advice of fellow actor Roddy McDowall, the pair started a nightclub act of songs mixed with conversational patter, titled "Michael Dunn and Phoebe." The act received favorable reviews in Time magazine and The New York Times and ultimately led directly to the pair being cast on The Wild, Wild West television series, a Western spy spoof with elements of historical fiction and science fiction, which debuted in 1965.7, 8

Dunn was probably best known—and received an Emmy nomination—for his recurring role on that series as Dr. Miguelito Loveless, a mad scientist who devised passionately perverse schemes and gadgetry to ensnare Secret Service agents James West and Artemus Gordon (Robert Conrad and Ross Martin). Dorin played Dr. Loveless's devoted assistant, Antoinette. In each episode, the villainous couple tenderly sang a Victorian duet or two, heedless of the mayhem they had created around themselves. According to Dorin, Dunn saved her from drowning during filming of the episode, "The Night of the Murderous Spring," plunging underwater to tear her free, when her costume became entangled in machinery used to sink a boat on the set.8

In the pilot episode of the Mel Brooks and Buck Henry television spy spoof Get Smart, Dunn showed his skill with comic farce as the well heeled gangster Mr. Big, leader of international crime organization K.A.O.S. (September 18, 1965). He also gained wide exposure in his role as Alexander, a courageous court jester, in the Star Trek episode "Plato's Stepchildren" (November 22, 1968). The role showed off both his dramatic and singing skills—as well as the scriptwriter's obscure knowledge of the Classics. (Alexander caps his solo about the Greek god Pan with a guttural, onomatopoeic quotation—"brekekekex, koax, koax"—from the Aristophanes comedy, The Frogs, written in about 405 B.C.) He was nominated for an Emmy again in 1970, for his portrayal of a recently widowed circus performer trying to start a new life, in a now-lost episode of Bonanza, "It's A Small World" (January 4, 1970).

On the live stage, in 1963, he received the New York critics' Circle Award for best supporting actor and was nominated for a Tony Award, for his role as Cousin Lymon in Edward Albee's intense stage adaptation of The Ballad of the Sad Café, by Carson McCullers. He also received an Oscar nomination and the Laurel Award as the best supporting actor for his role as the cynical Karl Glocken in Ship of Fools (Columbia Pictures, 1965, directed by Stanley Kramer). In 1969, The New York Times drama critic Clive Barnes praised Dunn's portrayal of Antaeus in the tragedy The Inner Journey, performed at Lincoln Center: "Michael Dunn as the dwarf is so good that the play may be worth seeing merely for him. Controlled, with his heart turned inward, his mind a pattern of pain, Mr. Dunn's Antaeus deserves all the praise it can be given."[10]

Between those career highlights, he accepted roles in many pulp horror movies. However, at the time of his death, he was in London playing Birgito in The Abdication (Warner Brothers, 1974, directed by Anthony Harvey), starring Peter Finch and Liv Ullmann. In addition, author Günter Grass had already asked him to play in a film adaptation of his novel, The Tin Drum, a role that ultimately went to the young David Bennent after Dunn's death.8

Dunn has been described as a ladies' man with a great deal of charm. He was married on December 14, 1966 to Joy Talbot, reportedly a burlesque dancer with mercenary motives. (Motion Picture magazine described her as a model, in a photo caption in the March, 1967 issue.) The union was unhappy and ended in divorce after a few years. He had no children. He developed into a dedicated philanthropist toward children with dwarfism who would write fan letters to him confiding their loneliness and despair. According to Dorin, Dunn often traveled to visit such children at his own expense, delivering encouragement to them and stern counsel to overprotective parents.1, 8

His mobility and physical stamina were poor and deteriorated throughout his brief life. He suffered especially from deformed hip joints (due either to hip dysplasia or coxa vara, with secondary osteoarthritis).1 However, he scampishly disguised his limitations by telling tall tales that a gullible press eagerly reported as the truth. Various accounts describe him as an aviator, skydiver, judo master, football player, and concert pianist, despite clear evidence on film of a severe, waddling limp, permanently flexed limbs, and gnarled fingers. In published interviews, he did hint at his childhood limitations both in football—"I was a great passer"—and in baseball: "I wasn't a very fast runner. I had to depend on sliding".7, 3 Working in New York, Dunn reportedly accrued masses of parking tickets, since disabled drivers had no special privileges. He also received human transport from friend and stuntman Dean Selmier, who often carried Dunn on his shoulders through the streets of Manhattan.1, 8, [11]

Spinal deformities including scoliosis caused a distorted ribcage that restricted Dunn's lung growth and function. The resulting respiratory insufficiency caused overload of the heart's right chambers, a chronic condition called cor pulmonale. He died in his sleep in his room at the Cadogan Hotel in London, on August 30, 1973, at age 38, while on location for The Abdication.

The New York Times reported his cause of death as undisclosed, leading to decades of repeated public speculation about possible suicide.10 However, the designation "undisclosed" signified merely that no cause of death had yet been determined. An autopsy was performed on August 31st, 1973, by a Professor R. D. Teare at St. George's Hospital in southwest London, who noted: "The right side of the heart was widely dilated and hypertrophied to twice its normal thickness. The left ventricle was normal in size." He recorded the cause of death as cor pulmonale.1 This information is confirmed in the "Report of the Death of an American Citizen" from the U.S. Department of State, Foreign Service, American Embassy in London, made out on October 12, 1973, by Micaela A. Cella, Vice Consul. The report is on record in the U.S. National Archives in College Park, MD.

A careless London physician named Bell likely hastened Dunn's demise, by prescribing and administering two narcotics and a barbiturate for severe arthritic pain, despite the extreme risk of inducing respiratory depression, apnea, and death in a patient with decreased respiratory reserve. Nonetheless, Dunn probably needed the drugs in order to tolerate the physical demands of shooting a movie. The autopsy's finding of intense vascular congestion in the lungs also suggests the possibility that a rapidly progressive pneumonia may have been developing.

Allegations of chronic alcoholism are unsubstantiated by the autopsy report, which notes only venous congestion of the liver—presumably secondary to Dunn's right-heart failure—without cirrhosis, and without inflammation of the stomach lining or pancreas. One consequence of such liver dysfunction would be jaundice. Another would be intoxication after drinking even small amounts of alcohol, as well as a toxic reaction to the prescribed drugs—either of which could also induce altered mental status (such as disorientation, delusions, faulty memory). This may explain the family's report that Dunn sent home a strange telegram "shortly before his death." ("I'm OK. The cops are looking.")5 Rumors of foul play and theft of the body are completely unsubstantiated by Scotland Yard.1

Remarkably, despite being severely ill and in great pain, Dunn continued working nearly up to the day of his death, living up to his own description of himself as "a both-feet jumper."6 He was buried September 10, 1973, in Lauderdale Memorial Park Cemetery, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, near his parents' retirement home in Lauderhill. In July, 2007, his remains were disinterred, shipped to Oklahoma, and reburied "near to" his parents' graves in Sunset Memorial Park Cemetery, Norman, Oklahoma. Three cousins took the action out of respect for the wishes of the late Fred (d. 1981) and Jewell Miller (d. 1990).5

|

1964 |

February

7 |

The

Jack Paar Program |

(interview) |

guest |

|

1965 |

August

3 |

Today |

(w/

Phoebe Dorin) |

guest

performer |

|

1965 |

September

18 |

Get

Smart |

pilot |

Mr.

Big |

|

1965 |

October

1 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night The Wizard Shook the Earth” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1965 |

November

19 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night That Terror Stalked the Town” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1966 |

February

18 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night of the Whirring Death” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1966 |

April

15 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night of the Murderous Spring” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1966 |

September

6 |

Today |

(w/

Phoebe Dorin) |

guest

performer |

|

1966 |

September

30 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night of the Raven” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1966 |

October

10 |

Run

for Your Life |

“The

Dark Beyond the Door” |

George

Korval |

|

1966 |

November

18 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night of the Green Terror” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1967 |

March

3 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night of the Surreal McCoy” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1967 |

March

5 |

Voyage

to the Bottom of the Sea |

“The

Wax-Men” |

clown

|

|

1967 |

April

7 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night of the Bogus Bandits” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1967 |

September

29 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night Dr. Loveless Died” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1968 |

March

22 |

Tarzan |

“Alex,

the Great” |

Amir |

|

1968 |

November

22 |

Star

Trek |

“Plato's

Stepchildren” |

Alexander |

|

1968 |

December13 |

The

Wild Wild West |

“The

Night of Miguelito's Revenge” |

Dr.

Miguelito Loveless |

|

1969 |

June

11 |

Personality |

(interview) |

guest |

|

1970 |

January

4 |

Bonanza |

“It's

a Small World” |

George

Marshall |

|

1970 |

August

20 |

The

Tonight Show |

(interview) |

guest |

|

1972 |

February

23 |

Night

Gallery |

“The

Sins of the Fathers” |

Servant

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

©2008 by Elisabeth Thomas-Matej, all rights reserved. Posted at RootsWeb.com with permission.

[1] Thomas-Matej, E., What’s in a diagnosis? A medical biography of Michael Dunn. 2002. The Wild, Wild West fan site of Hazard, Nebraska. http://www.nctc.net/hazard/conrad/michaeldunn/biography/

[2] Biography, Michael Dunn. Columbia Studios, Hollywood, CA; John C. Flinn, Studio Director of Publicity and Advertising. 1964, 4 August. http://www.wildwildwest.org/www/otherbio/md/md_bio.html

[3] Higgins, R. The only thing small about Michael Dunn is his height. TV Guide. 1967, 8 July:22-24.

[4] The Detroit News spelling bee: former champions. At: Rearview mirror: The Detroit News living history project. http://info.detnews.com/redesign/history/story/historytemplate.cfm?id=196

[5] Zizzo, D. Genius actor gets home at last. Daily Oklahoman. 2007, 17 July.

[6] Nachman G. The tall success of Michael Dunn. New York Post. 1965, 19 November.

[7] Bosworth P. Just an ordinary guy. The New York Times. 1966, 25 September.

[8] Weaver T. Interview with Phoebe Dorin. 2000. http://www.nctc.net/hazard/conrad/michaeldunn/dorin/

[9] Miller, Gary Neil: Application for Admission to The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, in the Province of St. Joseph (Provincialate: 1740 Mt. Elliott, Detroit 7, Michigan). 1957, 31 July.

[10] Michael Dunn, 39, the actor, is dead. The New York Times. 1973, 31 August.

[11] A dwarf’s full-size success. Life. 1964, 14 February.

This site may be freely linked, but not duplicated in any way without consent.

All rights reserved! Commercial use of material within this site is prohibited!

© 2000-2025 Oklahoma CemeteriesThe information on this site is provided free for the purpose of researching your genealogy. This material may be freely used by non-commercial entities, for your own research, as long as this message remains on all copied material. The information contained in this site may not be copied to any other site without written "snail-mail" permission. If you wish to have a copy of a donor's material, you must have their permission. All information found on these pages is under copyright of Oklahoma Cemeteries. This is to protect any and all information donated. The original submitter or source of the information will retain their copyright. Unless otherwise stated, any donated material is given to Oklahoma Cemeteries to make it available online. This material will always be available at no cost, it will always remain free to the researcher.